Episode 6: How to Save a Life – A User’s Manual*

By: D. Deonarain

*This blog draws its inspiration from those kinds of cases that keep you up at night thinking and those kinds of songs that you just can’t get out of your head…

Step 1: Take another little piece of my heart now, baby…

The commotion outside the tents woke everyone up. Just before, I had already slipped into that delicious half-sleep in the cocoon of my sleeping bag. My mind had been deep diving in the realm between dreams and consciousness when it was forced to resurface all too abruptly. I stared wide-eyed into the darkness of my tent. Flashes of light passed through the thin nylon walls and made me squint. Broken sentences in Sherpa echoed around me. Movement. Heavy footfalls. More shouts.

“Doctor?”

A hush. I listened.

“Doctor?”

I emerged from my cocoon and sat up. I listened again for a moment then called out.

“Are you looking for the on-call doctor?” There was an inevitability to the commotion. They were looking for me. I didn’t wait for a response. I was already emerging from my sleeping bag and slipping on my down layers. There was a medical emergency. That much was sure.

I passed from the vestibule out into the cold dark night. I was still fastening the zip on my down jacket when they opened the fly zip to my tent. Faces filled the widening crevasse and the cold night air slipped in.

“Doctor. We have patient… very weak.”

I stared out at the multitude of faces.

“OK. No problem. Bring him to the medical tent.”

“Not possible. Very weak. Not walking so good. You come.”

I knew this would not be a great option. I would be slow on the terrain whereas the Sherpa as a group, even laden with a patient could move much quicker than I could. Plus, I would be limited by what gear I could carry in the emergency bag. I stuck to my guns.

“Take the sked… Get six strong men and carry him here. It’s better. More equipment.”

A pause. The creaking glacier was the only sound now.

“OK. OK. We’ll do that.”

I couldn’t see from the faces who was answering me from the crowd, but it didn’t matter. We had a plan now and I had work to do. I emerged from the tent and illuminated my head lamp and walked over towards Pawan’s tent.

“Pawan… we’ve got a pretty sick patient coming. I think I’m going to need some help.”

A stirring from his tent.

“OK. I’m coming.”

There was no need for more chat. I knew he would be down soon. Pawan was in his second postgraduate year, just completing his service in remote areas for the Nepali government, but already he was a seasoned doctor, having seen much more clinically than others I had met at his level of training.

I headed out towards the clinic. The path to the clinic was only 200 metres but like all base camp it was a jumble of rock and ice and I was still bleary from sleep. I entered the clinic, powered up the Goal Zero generator, lit the proprane heater… and waited. Pawan arrived shortly after, bundled in down, his hair a wild tousle. We nodded, chatted only a little, prepared our equipment, and continued wait.

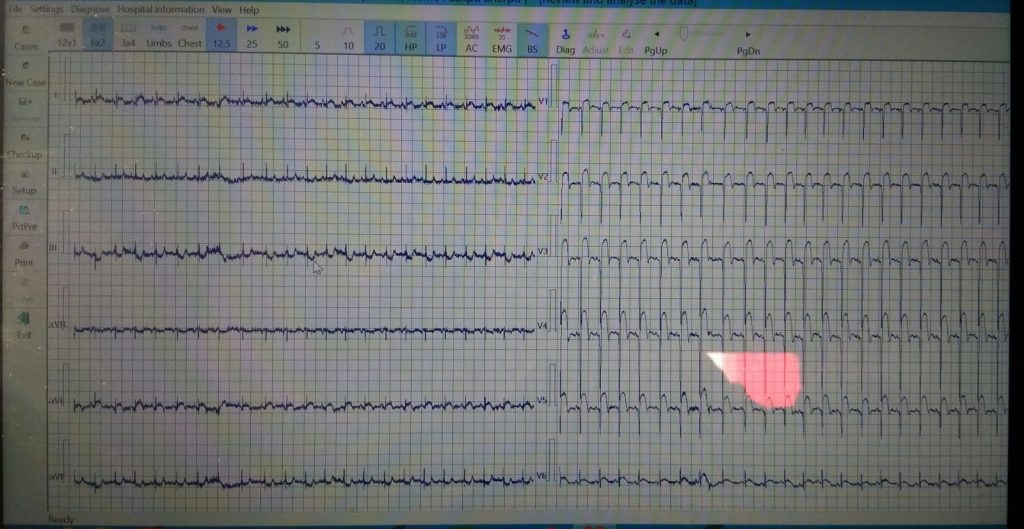

Before long they arrived: The four carriers to start and one Sherpa directing them in, followed soon after by a small army of Sherpa, maybe thirty souls crowding the medical tent. He was the Sirdar, the leader, and they paid respect for him in numbers. Pawan and I worked amongst the crowd and got the history from the middle aged, weathered Sherpa who was obviously weak and in pain. The history was obtained through questions in both Nepali and English and I did the examination. Strangely, the elements just didn’t line up. Nagging right subscapular pain, some very non-specific leg weakness, shortness of breath… We began to investigate— the vital signs were normal, his examination, unremarkable, an ultrasound sweep of his abdomen, aorta, heart, lungs – fine. Eventually we got the kit out for an ECG. It took awhile to set up, but Pawan was practiced at it. I connected the output to my computer and opened the ECG software. Pawan came around to me and we watched the screen together. The 12 lead output would record in real time and was about to receive the signal. It seemed an eternity. I grew impatient staring at 12 flat lines neatly labelled on my laptop screen…

…and then it came through.

Tombstones. Soaring elevation in the ST segments. Widespread. Yes, the rate was fast, but not so much so that this could be explained away as rate related ischaemic changes. This was an anterolateral ST elevation MI.

It was 10:49 pm. Helicopters were not equipped to fly in the Khumbu at night. We had no cold-chain, thrombolytics, or cath lab. His ‘door-to-needle’ or ‘door-to-balloon’ time would already be astronomically long… Everest, in many ways, is a cruel mistress. Our best and only chance to save this Sirdar would be to maximize his medical therapy, keep him stable, and evacuate him at first light… We had a lot of work to do and we needed luck on our side if we were going to pull this off.

Step 2: Free fallin’ now…

He unclipped from the fixed rope and took a few steps. They were awkward, not quite a stumble, but enough to be noticed by the others. He was a least a few metres from the fixed line when they started to yell. It was too late. He dropped away, through the thin air, past the blue ice… a four hundred metre fall down the Lhotse face.

I had to ask the story from the Sherpa at the helipad a few times. It couldn’t believe that anyone could fall that far and survive. It didn’t see possible. The Lhotse face was always known to be dangerous – sheer walls with blue ice – a gauntlet that Everest climbers had to run in order to summit. To fall at this point usually meant certain death.

I steadied myself, the heli was on approach. Many of the Sherpa left the helipad and scurried down the rock bank. I was here with a handful of Sherpa and Bruce, an American EMT from one of the climbing teams all huddled to the ground. The B3 helicopter roared on approach. The down draft of air blew the Khumbu dust in great billows. I tucked my chin into my jacket and pressed my googles into my face. No more time to theorize. It was time to work.

After the skids had touched down, the Sherpa that were with me approached the heli and opened the rear door. Many hands lifted the sked from the heli and delivered it to the ground. The patient was still well bundled in his down, but it was easy already to see the extent of his injuries. Massive head and facial injuries were visible despite the field bandages that had been applied. He was unconscious, but he was breathing.

We hunkered down again as the chopper powered up. With another roar, it was off, up again through the valley. We had ten minutes before the next, our rescue heli to Kathmandu would arrive. With few words, Bruce and I got to work. We sequentially moved over the patient with gloved hands and completed the primary survey: Airway – patent; c-spine controlled in a Sam splint, Breathing – equal chest rise and moving air well, no added sounds, Circulation – no massive haemorrhage noted, a controlled scalp wound, no signs that the chest, abdomen, pelvis, or limbs were pooling blood; Disability – some quick maths – E1V2M1, 4 – not good, L pupil sluggish at 4mm, R pupil not seen, the swelling over the eyelids had sealed it shut from all the presumed facial fracturing.

In the next moments, the rescue helicopter could be heard on approach. Shouts. Movement. A hunkering down again as the great machine lowered to ground. Hands. A hoist of the sked onto the chopper. I followed. My medical bag handed to me just before the heli door shut. A scatter of bodies as me, the pilot, and the dying man – our small trinity – were carried down the Khumbu valley, over the tent metropolis of base camp, south towards Kathmandu. I had only one job: Keep him alive.

Step 3: Closing Time… every new beginning marks another new beginning’s end

“Is it time to go?”

“You can stay if you like?”

I looked around. There was still a crowd. The gigantic geodesic dome tent was still full of people milling around. In the centre, a group of Sherpa, maybe 30 strong forming a circle of linked arms. They chanted in unison and stomped their feet. They were led by Tashi, the lead Sherpa from Mountain Professionals, his great fur hat denoting his status. I had only just broken away from the circle myself. I was still a bit breathless from the Sherpa dances and chanting. The host, Mike Hamill, accomplished climber and owner of ‘Climbing the Seven Summits’ mountain guiding company and this very dome, was chatting with a group of climbers off to the side. The atmosphere was still very lively. I was torn. Pawan and Deirdre were already making slow motions towards the vestibule exit. Pawan lingered a little, waiting for my reply.

“I really should go too, heh?” I couldn’t myself decide if that was a statement or a question, and if so, to whom. I’m normally not an indecisive person but the polarity of this decision was pulling at me strongly. The four strong gin and tonics I had made the self-service bar that the host had provided (dangerous, very dangerous) had already diffused well and truly into my system and pleaded with me to stay while the struggling sober conscious deep within me nagged that I was still at 5300+ metres and that one more drink would almost assuredly mean more problems… if not tonight, then tomorrow for sure at the clinic!

“You know… I’ll head back with you guys… another drink I think would really kill me!” I smiled wryly at Pawan and winked. I scanned the vestibule for my boots.

Sometimes the life that you save is your own.

Ain’t no party like a base camp party: Hanging out with Mike Hamill (centre). Everest ER doctor Deirdre on the far left and Adventure Consultant doctor, and good friend, Sara Gordon (right)

Dr Dinesh Deonarain is a Fellow of the Royal New Zealand College of Urgent Care who is in Nepal on assignment. He is volunteering for the Himalayan Rescue Association as one of the Everest ER base camp doctors for the 2019 climbing season. This blog follows his experiences in the high alpine of the Everest region.

Listen to the Profile in Urgent Care podcast with Dr Dinesh Deonarain.

If you would like to support Everest ER and the Himalayan Rescue Association, you can donate by bank transfer to: BNZ 02-0800-0196128-000. Also, you can follow Everest ER this season at www.EverestER.org

Boots on Everest – Episode 1

Boots on Everest – Episode 2

Boots on Everest – Episode 3 – Part 1

Boots on Everest – Episode 3 – Part 2

Boots on Everest – Episode 3 – Part 3

Boots on Everest – Episode 4 – Part 1

Boots on Everest – Episode 4 – Part 2

Boots on Everest – Episode 5