Episode 3, Part 1: Up

By: Dr Deonarain

“Marthula?”

“Yerkela.”

“Tala?”

“Yerkela!”

Mingma was smiling broadly. His right hand angled up towards the snowy peaks, impossibly high. We both laughed. Up. Always up.

When you’re on the trail to Everest, up is the most likely direction, if you had to wager. We had been the trail for three days now. We still had a long way to go.

Everest Base Camp sits at 5364m. That is 1.5 kilometres higher than the top of Mount Cook and twice the height of Mount Ruapehu. To get there it takes time, patience, resilience and effort. I’d had experience of the high alpine of Nepal on two other occasions but this seemed to have little bearing. My body was slow to recall the elevation it had known before. I had to concentrate on my breathing and heart rate to ensure that I didn’t ‘redline’ and find myself doubled over my trekking poles gasping at whatever air I could.

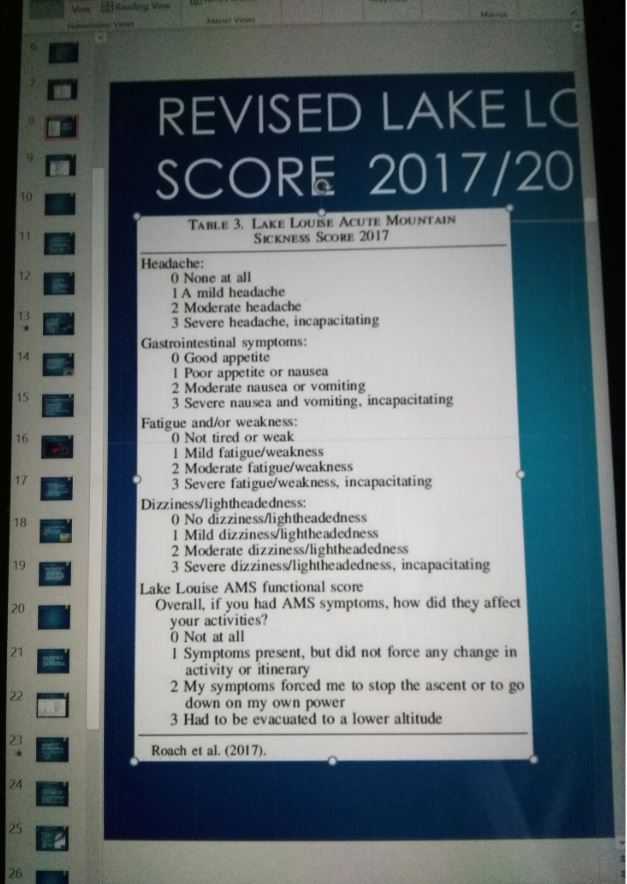

Scoring altitude sickness

The memorial at Pheriche to climbers lost on Everest

Altitude is a sneaky devil… and it can catch you in many ways. To stay ahead of this devil, it pays to know a little physiology. Basically, as you ascend, the pressure of oxygen in the air diminishes. The body reacts by breathing faster in order to clutch at whatever oxygen it can. This of course tops out at a point when you find yourself in a state of respiratory alkalosis. At this point, the kidneys kick in to help and try for an offset. This comes in the form of a bicarbonate diuresis. Quite simply: a pissing frenzy. (Pardon my French.) This pushes the blood pH down once more and the resulting metabolic acidosis which once again stimulates breathing. This physiological spinning wheel trundles you along as you go up and works quite well, but with a prophetic warning lying beneath, worthy of a Shakespearean drama: Go slow… or sickness shall thee feel.

So, how does the devil of altitude catch those who don’t pay heed to the warning. Ascents greater than 500m per day at altitude (usually above 2000m) puts your spinning wheel of physiology into a wobble. You can no longer urinate or breath fast enough to remain in homeostasis in the thin air. The pulmonary vasculature tightens and the cerebral vasculature slackens. This results in leaks. Fluid collects in the brain and lungs and symptoms come in droves. Headaches, nausea, GI upset, sleep disturbance, diminished exercise tolerance, shortness of breath, cough, to name a few. This constellation of symptoms is in the galaxy known as AMS, or acute mountain sickness. If allowed to progress, conditions such as HACE (High Altitude Cerebral Edema) and HAPE (High Altitude Pulmonary Edema) arise—the worst devils of all. Many great mountaineers have succumbed to these fiends. Scott Fisher, the talented American climber and part of the doomed 1996 Everest summit bid fell asleep at altitude with lungs full of fluid. His HAPE progressed through the night and he was dead by morning—drowned from the inside. I’ve watched chilling videos of climbers stumbling around like drunks at soaring altitudes, clearly victims of HACE. More so, I’ve seen both these conditions first hand; treated and evacuated scores for the same… and this is what I’ve been asked to do once more, this time at Everest, the highest mountain in the world. The last thing I wanted was to be a patient myself.

“Yerkela! Yerkela!” Mingma playfully patted me on the back, still the impossibly broad smile on his tanned face.

“Yes… but ‘bistarai’” I said, between puffs.

“OK. Yes. Bistarai.” Mingma replied with a slightly more somber countenance.

Slowly. Up, yes. But slowly.

Dr Dinesh Deonarain is a Fellow of the Royal New Zealand College of Urgent Care who is in Nepal on assignment. He is volunteering for the Himalayan Rescue Association as one of the Everest ER base camp doctors for the 2019 climbing season. This blog follows his experiences in the high alpine of the Everest region.

Listen to the Profile in Urgent Care podcast with Dr Dinesh Deonarain.

If you would like to support Everest ER and the Himalayan Rescue Association, you can donate by bank transfer to: BNZ 02-0800-0196128-000. Also, you can follow Everest ER this season at www.EverestER.org

Boots on Everest – Episode 1

Boots on Everest – Episode 2